training resources

Roles & Responsibility of the

Occupational Therapist in Early Childhood - Handicapped

by Susan Knuth, O.T.R.

Introduction

Occupational therapists (OT's) work with school-age and younger children who display a variety of handicapping conditions in birth to three educational settings and public school programs. OT services may be provided on a direct treatment (e.g., "hands on") or consultative model either in the child's home or at the school or center program. The child seen by en OT in these settings might have cerebral palsy, a learning disability, Down's Syndrome or other genetic disorders, orthopedic handicaps, myelomeningocele (spina bifida), or generalized developmental delay. In treating these children, the occupational therapist would address the child's needs in a variety of domains - commonly including oral-motor/feeding skills, sensory integrative function, fine motor development, perceptual motor skills, adaptive equipment needs, activities of daily living, and upper extremity splints.

Working closely with the parents, the special education or classroom teachers, and other therapists/specialists involved (e.g., PT's and speech and language pathologists), the OT would modify treatment, as needed, based on the child's unique needs and taking into account how the child's needs might change over time. For example, an observer in an early childhood exceptional education program might find the OT working with a child with cerebral palsy at snack time in order to improve the child's oral motor coordination needed for feeding. Or they might see evidence of special utensils (e.g., cut out cups, built up handle spoons, etc.) that will enable the child to feed him/herself. At the elementary level, the occupational therapist might be observed swinging a child with a learning disability in a net hammock or providing specific tactile stimulation in an effort to help the child organize and use the sensory information from his/her world more effectively. On a consultative model at the elementary level, the OT might offer suggestions to the teacher and/or parents regarding adapted techniques or clothing design that may enable the child confined to a wheelchair (e.g., due to spina bifida or cerebral palsy) to dress him or herself independently. At the upper elementary or secondary level, the OT might consult with teachers or vocational specialists regarding adaptive equipment or techniques that will help the student to be more independent in more specialized classroom situations. Topics addressed, for example, may include how the home economics student who is in a wheelchair, efficiently and safely reach the stove, set the table, etc. How can we make operating machinery in industrial arts safer for the student with a perceptual deficit that makes him/her inclined to neglect things off to the left? Will a special keyboard cover or other device (e.g., MOL,-Tx, sticks, etc.) allow the student with cerebral palsy to type into a computer keyboard more accurately?

Definitions

The American Occupational Therapy Association has adopted the following general definition for licensure purposes:

Occupational therapy is the application of occupation, any activity in which one engages, for evaluation, diagnosis and treatment of problems interfering with functional performance in persons impaired by physical illness or injury, emotional disorders, congenital or developmental disability, or the aging process in order to achieve optimum functioning and for prevention and health maintenance. Specific occupational therapy services include, but are not limited to, activities of daily living (AU); the design, fabrication and application of splints; sensorimotor activities; guidance in the selection and use of adaptive equipment; therapeutic activities to enhance functional performance; prevocational evaluation and training; and consultation concerning the adaption of physical environments for the handicapped. These services are provided to individuals or groups through medical, health, educational and social systems (Hopkins & Smith 1978, p. 707).

This broad definition covers the OT's varied roles in hospitals, schools, mental health centers, nursing homes, sheltered workshops and a variety of specialty programs/centers (e.g., burn units, group homes, correctional facilities, chemical dependency programs and private practice). The Education for All Handicapped Children Act, Public Law 94-142, defines occupational therapy as one of the related services to be used to meet students' individual educational needs. In its definition of related services, the law states, "occupational therapy includes: 1) improving, developing or restoring functions impaired or lost through illness, injury or deprivation; 2) improving ability to perform tasks for independent functioning when functions are impaired or lost, and; 3) preventing, through early intervention, initial or further impairment of loss of function.. The American Occupational Therapists Association (ROTA) supports the definition of occupational therapy as an education-related service necessary to assist handicapped students to benefit from special education (Occupational Therapy, 1981, p. ).

Important components of this definition include the fact that OT is a related service--that is, a student must be eligible for an exceptional education program in order to receive OT or other related services. OT cannot be the only special service provided to a student in the public schools. The eligibility for exceptional education services, along with any recommendation for OT or other related services is determined by the M-Team. An OT may act as a member of the M-Team. Additionally, OT services must be educationally relevant or "used to meet the student's individual educational needs," for example, the OT services for a child might focus on improving general perceptual and fine motor skills in order to improve the child's handwriting skills so he/she can participate more effectively and efficiently in the classroom activities and assignments.

Education, Certification Licensure and Recertification OT's typically have gone through a bachelor of science degree program that takes a little over four years to complete. Typical coursework includes a variety of science courses (anatomy and physiology, neuroana tomy and neurophysiology, neurology, pathobiology, musculoskeletal anatomy, sensory integration, etc.), various psychology classes and methods classes (e.g., biomechanics, rehabilitation of the hand, group dynamics, etc.) In addition to coursework, the occupational therapy students must complete two different levels of fieldwork placements such as in hospitals, clinics and schools in two types of treatment programs, physical medicine and psychosocial treatment programs. At the first level, what is typically referred to as a practicum placement, the OT students spend 40-50 hours over the course of a semester working directly with an experienced registered occupational therapist (OTR) in a psychiatric and physical medicine/rehabilitation. At the next level, or affiliation placement, the OT students have completed nearly all their coursework and are ready to work full time in a hospital/clinic setting under the supervision of an OTR for three months in each of the two areas. A third affiliation is optional but may be done for 2-3 months in a specialty area such as pediatrics, geriatrics, or chemical dependency. As indicated earlier, the academic fieldwork preparation to become an OTR is usually done at an undergraduate level; however there are several programs that offer what is referred to as basic masters, or "certification" programs which offer professional preparation at a graduate level for students who have bachelor degrees in other fields. There is also an elaborately outlined set of requirements (academic and experience) that a certified OT assistant can meet and essentially work towards becoming an OTR.

After completing the academic and fieldwork requirements, the potential OT must still take and pass the national registry examination. A passing score on the registry exam allows the therapist to use the designation, ‘0TR,’ following his/her name. Registration through the American Occupational Therapy Association, must be renewed annually at a cost of $65.

Additionally, a passing score on the national registry exam is used, in most states, as at least part of the requirements for state licensing as an OT. In Wisconsin, occupational therapy is not yet a licensed profession. Instead, Wisconsin relies on the requirements of outside agencies' rules and regulations (e.g., the Joint Commission of Accreditation of Hospitals, requirements of third party payers and insurance companies, Department of Public Instruction, etc.) to insure that OT services are provided by qualified therapists.

In addition to meeting the above qualifications, an OT must meet additional requirements to work in the public schools in Wisconsin. This involves an additional nine college credits in special education and application to the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction for certification 812. This is roughly comparable to teaching certification in Wisconsin with requirements for continuing education and renewal every five years.

Professional Organizations and Publications

The American Occupational Therapy Association (ROTA) is the national organization for OT's. In addition to being the agency that registers OT's, ROTA publishes several periodicals and sets professional ethics and standards of practice in all areas of practice (see appendices A and B for those related to school based therapists). Additionally, as a member of ROTA, the therapist may also belong to one of a number of special interest sections (SIS). Most school based therapists belong to the developmental disabilities SIS or sensory integration SIS. The SOS's also publish their own quarterly newsletters.

In Wisconsin, OT's may also belong to the Wisconsin Occupational Therapy Association (NITS). However, WOTA membership is not mandatory. WITS is further divided into four districts to facilitate regular meetings, etc. WOTA is currently very active in trying to establish a state license for occupational therapists in Wisconsin.

Publications typically used by OTs include the American Journal of Occupational Therapy, Occupational Therapy News, OT Week, and SIS Newsletters (all published by ROTA), OT Forum, Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, Research in Occupational Therapy, and Occupational and Physical Therapy in Pediatrics.

The Occupational Therapist in the Public Schools

In the special education setting, the OT provides evaluation, treatment, and/or consultation in a number of areas (to be discussed later). The OT participates as a member of the 0-Team or E-Team and helps to develop the NIP for a child. Additionally, the OT often acts as a liaison with the medical community through renewal of annual prescriptions and discussion of needs for adaptive equipment or special needs following surgery, etc.

In the school setting, as in many other facilities, there are some generally agreed upon distinctions between roles of OT vs. PT (sometimes speech therapy). However, there is often overlap of some roles and responsibilities, and decisions as to who will do what is dependent on a number of factors

including facility tradition, availability of staff, and differences in therapists' training and experience. It is hoped that decisions regarding specific roles and responsibilities are made largely depending on the individual therapist's training and experience; for example, if the occupational therapist has been certified in neurodevelopmental training and physical therapist has been training in sensory integration. The resulting division of roles might be very different than in a setting where the reverse is true. Outlined below are some generalizations regarding traditional division of roles and comments regarding shared roles of OT and PT (see Appendix C).

Roles Typically Assumed by Occupational Therapist in the School Setting

OT's frequently evaluate and develop programs for children with oral-motor and/or feeding dysfunction. (This role might also be shared with speech and language therapists depending on training and experience.) Oral-motor and feeding dysfunctions are often seen in multihandicappcd young children, with cerebral palsy being perhaps the biggest cause of feeding disorders of this nature. Because these problems are often seen in CP children, the therapy approach for feeding problems often incorporates much of the treatment principles of neurodevelopmental treatment in general. Evaluation of oral motor and feeding problems is largely observational and involves a large number of factors. Both evaluation and treatment can cover a range of skills from chewing and swallowing up to self-feeding. Components addressed by the OT includes a) general movement and positioning components (e.g., is the child able to sit and hold his head at midline? do primitive reflexes like ATNR interfere with good position); b) review of pertinent medical history (is the child likely to aspirate? or have a history of reflux?); c) sensory factors (is the child unusually sensitive to touch in or around his/her mouth?); and d) oral structure and function (does the child have a gag reflex? can he/she close his mouth? move jaw or tongue up and down and side to side? is the child's palate highly arched, etc.). Additionally the therapist may look at the appropriateness of adaptive feeding equipment to enable the child to be fed or feed herself more safely and efficiently. For example, will a cut-out cup allow the child to drink without throwing his head way back? Will a bent handle spoon allow the child to get the food to his/her mouth with less spilling?

Activities of Daily Living (ADL's) is another area the OT may evaluate and treat or provide consultation to the classroom teacher. Evaluation is typically observational and based on checklists. This is a broad area including self-care (dressing, feeling/eating, grooming/hygiene, mobility, object manipulation, and communication), work skills (home management skills and job related skills) and vocational skills (play/leisure, community utilization, etc). The OT's expertise in these areas may have particular relevances for students with physical limitations (CP, spina bifida, artmitis, amputers) or perceptual disorders (e.g. unilateral neglect). In addition to looking at ADL's in terms of the student's capabilities, the therapist may look at the environment and possible modification to enable to the child to function more independently. Range of services to children in this area may include teaching the child to handle clothing fasteners, modification in clothing design appro-priate for a wheelchair-bound child, training in one-handed techniques, using adaptive equipment to compensate for physical limitations (e.g. using reachers to allow the child in a wheelchair to get materials off a shelf) or training in energy conservation/work simplification. The OT also deals with muscle tone (e.g. either too "tight" or too floppy) and strength disturbances of the childs upper extremeties and trunk. Evalua-tion typically involves observation of the quality of a childs movement, espe-cially as noted as part of the child's regular routine or participation in activities. For example, the child with cerebral palsy may be able to straighten his arm at the elbow only when he throws his head back. The ataxic child may show less instability in his movement in activities like playing with clay where there is more resistance and stability. Depending on the specific nature of the problem, treatment may overlap with other areas, for example, neurodevelopmental or sensory integration approaches to increase or decrease apparent muscle tone, as needed. Following these attempts to .normalize" muscle tone, the therapist would present a variety of functional activities to allow the child to find more normal movement patterns. The therapist might provide weights for the ataxic or midly low tone child to wear for specific activities. The area of treatment probably most often associated with occupational therapy in school settings is the remediation of fine motor or manual dexterity problems associated with a wide variety of handicapping conditions. The therapist say assess these skills using a variety of norm referenced and/or crite-rion referenced checklists like the Peadbody Developmental Motor Scales, Learning Accomplishments Profile, or Early Intervention Development Profile. The therapist might also look at specific prehension patterns using Eidhart's Developmental Prehension Assessment. Or the therapist might look at speed and accuracy of the older student's manipulation using standardized assessments like the Purdue Pegboard or the Minnesota Rate of Manipulation. Fine motor deficits are often identified by classroom teachers due to the relationship with handwriting. Treatment of fine motor problems includes positioning and handling to improve function, practice with a variety of increasingly difficult manipulatives following a developmental sequence, or adaptive equipment or techniques to compensate for difficulties (e.g. built up writing intensils, typing with a mouthstick, etc.). Perceptual-motor deficits are another area often treated by OT's. This may be viewed as a part of tho more comprehensive area of sensory integration. However, specific perceptual problems may be seen, apart from sensory integra-tive dysfunction, in the older child who suffers a traumatic brain injury. Examples of such problems might include visual field deficits (e.g. not seeing things off to one side), unilateral neglect (especially ignoring the left side of the body), deficits of visual figure ground or spatial relationships. Treatment typically focuses or pracific with specific skills and attempts to generalize skills. Compensatory techniques may also need to be taught, for example, color coding the left side of the page to cue a student with left unilateral neglect to return to the beginning of the line in reading.

Roles and Functions Shared by Occupational and Physical Therapists

Adaptive equipment needs are an area of overlap for OT and PT. While the PT might be the one to offer asistance for large positioning and/or mobility needs (e.g. walker, wheelchairs, pronestanders, etc). The OT might better be able to recommend adaptize equipment or aids for fine motor skills or ill skill components. Examples include devices to allow the child to dress independently from a wheelchair, reachers to allow the child to get materials off a shelf, special utensils or devices for feeding, mouthsticks or other adaptations for typing. With respect to orthotics (e.g. splints) or prosthetics, the OT deals with these particularly as they relate to upper extremity function, which includes training it in the use of prosthetic arms. The OT is also likely to design and fabricate hand splints that may position the child's bond and wrist so he/she can use it as a more coordinated fashion or a splint to be used at resting times to maintain range of motion is the hands and/or arms. Part of the OT's responsibilities with respect to orthotics is to provide teachers and parents with detailed instruction regarding putting the splints on, when the splints should be worn, and care of the splints when they are off. dritten instruc-tions are highly preferred. Because the children we work with may have a number of special medical or physical needs associated with their diagnosis, their ability to function in the classroom will be affected. This is especially true of the multiply handi-capped child. Some examples of functional limitations that OT and/or PT may be able to provide help with include poor endurance (e.g. associated with cardiac disorders or rheumatoid arthritis), unusually poor respiratory functioning, and special positioning considerations because of gastrostomy tubes or ostomy bag.

The OT might suggest work simplification or energy conservation techniques to deal with problems of poor endurance, or to protect fragile joints. The PT may suggest a positioning or postural drainage program to improve a child's respiratory functioning. Either the OT or PT could provide modifications for positioning to accommodate medical appliances. Reflexes and responses are addressed by both the PT and the OT's in treatment, because their presence for longer than usual or their absence can have profound affects on many of the other areas traditionally addressed by each discipline. For example the PT may be concerned about integrating the assymetrical tonic neck reflex (ATNR) or "fencer's posture" of a child with C.P., because until the ATNR is integrated or has disapproved, it will be difficult for that child to attain the gross motor skill of rolling. The OT will also work towards integrating this persistent ATNR because its presence will intefere with the child's ability to accurately reach and grasp or to feed himself. Sensory Integration (SI) therapy is a treatment theory and approach deve-loped by A. Jean Ayres which is likely to be used with learning disabled chil-dren. It's use is probably more prevalent among OT's than PT's. Because of the complexity of evaluation of treatments with this approach, it is recommended that therapists using this approach have specialized training. Assumptions of this theoretical approach include that sensory information must be processed or integrated appropriately within the child's central nervous system in order to be used effectively. Ideally SI therapy will help the child to process or integrate sensory information at lower levels of the central nervous system (e.g. brainstem level) so that the child does not have to "waste" cognitive efforts trying to make sense of basic sensory input. A commonly identified SI dysfunction is tactile defensiveness (e.g., the child is felt to be overly sensitive to normal touch or his nervous system is integrating most touch as threatening). This will affect the child's willingness to manipulate (and hence learn about) objects and/or his/her ability to function in a large or close group. The therapist would use carefully graded tactile stimulation in an effort to help the child organize and use tactile feedback more effectively. Another theoretical approach for which additional training is recommended for OT's and PT's is the use of new developmental treatment (NDT). This approach has been developed by the Bobaths and is used particularly with chil-dren with cerebral palsy. Treatment focuses on positioning and handling to promote optional muscle tone (e.g. to reduce or lower tone of the child is spastic) and to facilitate more normal movements patterns.

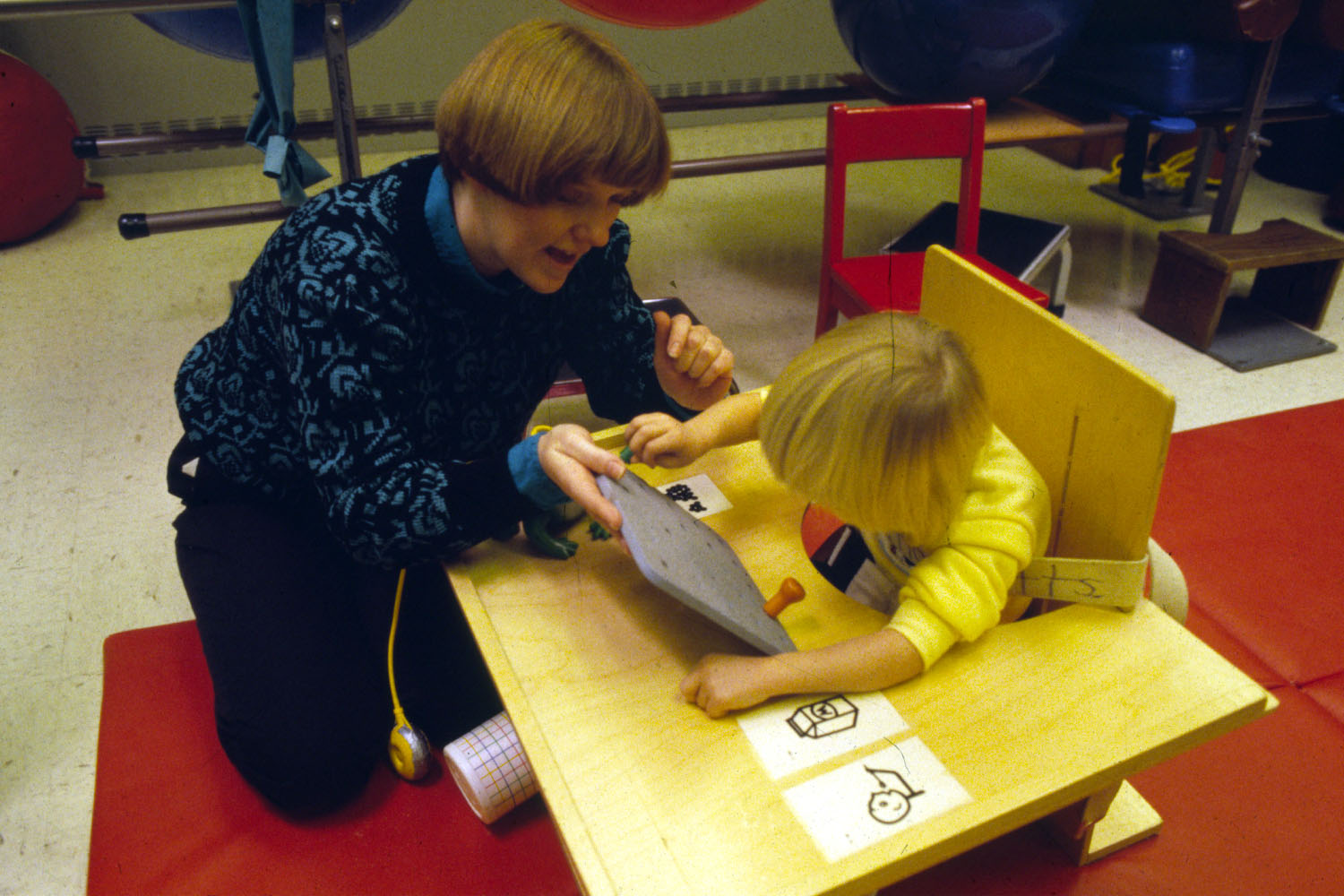

Occupational Therapist providing support to decrease hyperextension while using hand-over-hand assistance.

Franks, David J., & Franks, Catherine A., 1981, Occupational Therapy

Back to the top | Next: School Psychology >